A Bony Puzzle

The English word "skull" comes from skalli, the Old Norse word for "bald." Clever name. But the skull is rather clever, too. It is actually a structure comprised of 22 bones that fit together like pieces of a puzzle at immovable joints called sutures. The skull is clever because of what it can tell us.

First, however, let's go over some of the basics. The foramen magnum is the big hole at the bottom of the skull through which the spinal cord passes.The cranium is the skull without the mandible (lower jaw bone). The calvaria, or "skullcap," is the upper part of the skull, including the frontal bone (forehead), parietal bones (top of the head), and the occipital bone (back of the head). The splanchnocranium is the face, containing 14 bones, including the mandible (lower jaw bone). The temple is made up of the temporal bones and the tiny ear ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes) that help you hear. There are also miscellaneous bones that overlap between these regions, as well as sinuses, to bring the total to 22. Teeth, though, are excluded.

My favorite thing about the skull is its role in the biological profile. In biological anthropology, this profile is the life history of an individual, including biological sex, approximate age at death, ancestry, stature, and personal features (evidence of bone surgery, dental work, fractures, etc).

Biological Sex

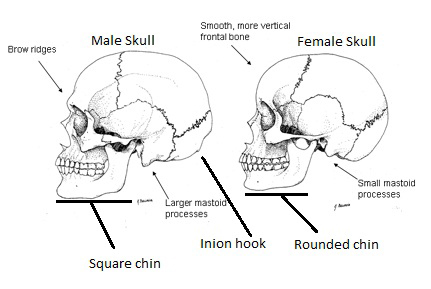

It is possible to determine whether a person is male or female from the skull, though having a relatively intact pelvis allows for a more accurate determination. However, if only the skull is available, as is sometimes the case in forensic anthropology and bioarchaeology, there are certain key things to look for.

In general, male skulls are larger and more rugged than female skulls, and their muscle attachment sites are more robust. Males have more pronounced brow bones/ridges, an angled or receding frontal bone (forehead), larger mastoid processes, a square-shaped chin, and an inion hook (a projection off the occipital bone--the back of the skull). Females, on the other hand, have small or absent brow bones/ridges, a vertical and slightly rounded frontal bone (forehead), smaller mastoid processes, and a smooth occipital bone (back of the head) that is free of projections--i.e. no inion hook. Of course, few individuals conform to these guidelines exactly. Some biological males will have some female features and vice versa, so whenever possible, anthropologists use the pelvis to corroborate their findings.

Age at Death

Our bones, including our skull, show our growth history. Infants and toddlers have gaps between their skull bones called fontanelles. As the child ages, the bones fuse together at the sutures, and by about 7 years old, the fontanelles are completely closed. Children also have deciduous (baby or primary) teeth, whose growth and loss stages can be predicted. Older children, adolescents, and adults have skull bones that are completely fused at the sutures, and their deciduous teeth are either being lost or are completely replaced by permanent (adult or secondary) teeth. This second wave of tooth growth also occurs in timed stages, and the presence or lack of third molars (wisdom teeth) is often an excellent indicator of age. Forensic anthropologists and bioarchaeologists use these growth charts to assign the approximate age at which the individual died. Such estimates will be more accurate for toddlers, children, adolescents, and young adults than for older individuals, as tooth growth stops after the third molars and tooth loss occurs unpredictably in the older adults (though the first and second molars are often the first to go).

Ancestry

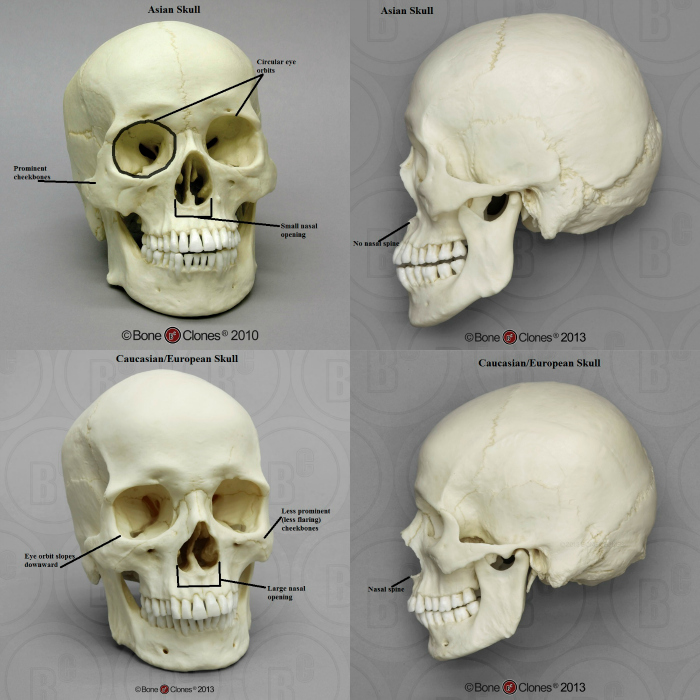

There is much contention about the skeletal features used to determine a person's ancestry. Some believe that biological race does not exist, that one cannot ascertain where a person's ancestors came from based on their bones. Others disagree. In my experience, using both gross morphological features and craniometric (measurements of the cranium) analysis, it is possible to accurately determine ancestry. However, Hispanics and those of recent dual ethnicities are trickier, as their skulls show a combination of both ancestries' features. Despite the mixed views, most forensic anthropologists still use ancestry as part of the biological profile.

Because this article is not meant to be an exhaustive discussion on osteology (the study of bones and their diseases), I'm just going to cover two potential ancestries--Caucasian/European and Asian. As with biological sex, the following identifiers are general and vary somewhat between individuals of the same ancestry, which is why a craniometric analysis is crucial.

Features of Caucasian/European skulls:

- Large nasal bones

- Eye orbits that slope downward

- Prominent nasal spine (the thin bone that partly bisects the nasal opening)

- Long, narrow nasal opening

- Sharp inferior (bottom) nasal border

- Receding cheekbones

- Blade-shaped incisors (front teeth)

Features of Asian skulls:

- Narrow, concave nasal bones

- Circular eye orbits

- Less prominent nasal spine

- Smaller, sometimes wider nasal opening

- Prominent, "flaring" cheekbones

- Shovel-shaped incisors

References:

1. White TD and Folkens PA. 2005. The Human Bone Manual.