The City of Spices

Istanbul, the city where Europe meets the Middle East. Yet despite this melting pot of nationalities and religion, the food is distinctly Middle-Eastern. Spices, red lentils, and olives reign supreme, as do beef and lamb. It's a flavorful place that I simply must return to.

Lavaş

I'm going to begin with a staple of nearly every diet in the world: bread. But not just any bread. A special type of flatbread that the Turks like to fill with air so that it blows up like a balloon during baking. This creates a hollow bread that is entirely crust, which is crispy on the outside and soft on the inner skin.

Lavaş actually originated in Armenia, where it is eaten like traditional flatbread, but the Turkish people have adopted it as a beloved part of their cuisine. It transforms the generic "bread plate" or "bread basket" into something fun, and when I first saw the server bringing it out, my eyes widened and I grinned. Sprinkled with black sesame seeds, lavaş is served with various Turkish cheeses, butter, and Turkish olive oil, as well as with typical Turkish breakfast foods, such as eggs and yoghurt.

Beyaz Peynir

Like its cousin feta, this firm, white, generally sheep's milk cheese is brined. But unlike its cousin feta, beyaz peynir lacks that distinctive tang, making it milder but also saltier. Some restaurants in Istanbul refer to it as "Turkish feta," so that it would be less alien-sounding to tourists, but I actually think it's superior to feta cheese (and I quite like feta). The Turks often eat it with bread for breakfast, but they also consume it in salads and cooked foods. When I was in Istanbul, many restaurants served beyaz peynir alongside lavaş bread.

Acılı Ezme

This spicy mashed tomato, onion, and herb concoction is eaten with bread as a dip or as a salad. Sometimes different lettuces are added to make it more akin to a salad, but I only encountered it as a dip for the lavaş bread. It may look a little dubious, as it is mashed, raw tomatoes, but with a little olive oil and the not-so-flat flatbread, it's actually rather delicious.

Çoban Salatası

Consisting of chopped tomatoes, cucumbers, red onions, green peppers (sometimes spicy!), lots of flat-leaf parsley, olive oil, and lemon juice on a bed of lettuce (usually romaine), çoban salatası ("shepherd's salad") is simple but tasty. I would even go so far as to name it one of the best salads I have ever eaten, and that's saying something, because I've eaten a lot of really good salads. Although it resembles Greek salad, sans the feta cheese, it is uniquely Turkish. Shepherd's salad is ubiquitous in Istanbul for a reason. The fresh, green flavor of the parsley and the tang of the lemon juice are necessary to cut through the heavy, spice-laden beef and lamb dishes.

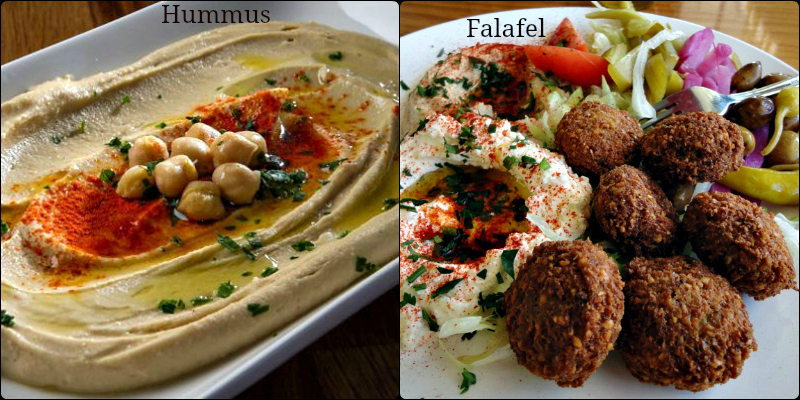

Hummus and Falafel

I'll be honest. Before I went to Turkey, I despised all-things chickpea. In fact, hummus ranked highest on my hate list. I thought it was bland, in both color and flavor.

Then I went to Turkey and wow did my opinion change. Full of garlic and spices, the hummus they served me in Istanbul bore little resemblance to its American impersonator. I was shocked that I liked it, yet upon further reflection, I really should not have been. From my previous culinary adventures in Istanbul, I should have expected that the hummus, too, would agree with my Hungarian palate.

As for the falafel, Istanbul made me love it. Ground chickpeas are mixed with onion, lots of garlic, cumin, coriander (the spice, not the herb), paprika, lots of parsley, and a binding agent (eggs, flour, or breadcrumbs). The falafel balls are fried and served with flatbread, a mix of raw and/or pickled vegetables (e.g., crispy brined red cabbage, cornichons, cucumbers, and shredded carrot), hummus, and various sauces (tahini, garlicky yoghurt, hot pepper).

Mercimek

I think lentils are a staple in most European and Middle-Eastern cuisines, which is to be expected, since they have been consumed since Neolithic times (9,000-13,000 years ago). There are about a dozen varieties in multiple colors, but the Turks prefer red lentils. While brown, green, and yellow lentils are quite mild, red lentils tend to be a little bitter. Turkish cooking offsets this with generous amounts of cumin, Aleppo pepper (a salty, fruity, and mild pepper that resembles ancho chili in flavor), and sometimes a spritz of lemon juice. A thick, puréed soup is the most common way to eat red lentils, and I ate it every day, sometimes twice a day. In fact, I now like red lentils better than the brown and green lentils that Hungarians cook.

I think lentils are a staple in most European and Middle-Eastern cuisines, which is to be expected, since they have been consumed since Neolithic times (9,000-13,000 years ago). There are about a dozen varieties in multiple colors, but the Turks prefer red lentils. While brown, green, and yellow lentils are quite mild, red lentils tend to be a little bitter. Turkish cooking offsets this with generous amounts of cumin, Aleppo pepper (a salty, fruity, and mild pepper that resembles ancho chili in flavor), and sometimes a spritz of lemon juice. A thick, puréed soup is the most common way to eat red lentils, and I ate it every day, sometimes twice a day. In fact, I now like red lentils better than the brown and green lentils that Hungarians cook.

Kebap

Or kebab, to us English-speakers. There are dozens of varieties, from ground lamb to beef chunks, but probably the most well-known variant is the döner kebap. Beef, lamb, or chicken is cooked on a vertical rotisserie, shaved onto flat lavaş bread or pita bread, and accessorized with all sorts of condiments (yogurt sauces, tahini, hot sauces), vegetables, and sometimes cheeses (like Istanbul's specialty, kaşarlı dürüm döner). Greeks have their own version--the gyros--, as do Arabic peoples--the shawarma, but those are just the more familiar types. Many Eurasian and Middle-Eastern countries have some sort of kebab that is native to them. And with such a yummy combination of ingredients, who can blame them?

Köfte

One cannot write about Istanbul's food without mentioning the Turkish meatball. Actually, to be more exact, köfte is not solely Turkish; Balkan (Bulgarian, Croatian, Greek, and Macedonian), Arabic (Syrian, Lebanese, Moroccan), Central and Eastern European (Slovenian, Romanian, Serbian), Middle-Eastern (Israeli, Afghani, Pakistani), and Indian cuisines all have their own variants. And then, of course, there's the Italian meatball, which does not quite seem to fit with the others. But that's irrelevant to this article.

One cannot write about Istanbul's food without mentioning the Turkish meatball. Actually, to be more exact, köfte is not solely Turkish; Balkan (Bulgarian, Croatian, Greek, and Macedonian), Arabic (Syrian, Lebanese, Moroccan), Central and Eastern European (Slovenian, Romanian, Serbian), Middle-Eastern (Israeli, Afghani, Pakistani), and Indian cuisines all have their own variants. And then, of course, there's the Italian meatball, which does not quite seem to fit with the others. But that's irrelevant to this article.

Although there are regional differences, the foundations are the same: meat (usually beef or lamb), spices (cumin, chili pepper), starch (bulgur or rice), and egg (to bind). Some cultures, like the Turkish, grill the meatballs; others bake, fry, or even steam them. Köfte is often served with some type of sauce, such as a spicy red sauce or a cool yogurt sauce.

Bodrum Çökertme

I've saved the best for last. For those of you who read my "Euro Travels" column, the name of this dish may look familiar, as I have previously sung its praises. Hailing from the city of Bodrum (in Turkey's Aegean region), this meat dish consists of beef or lamb strips that are cooked with onion, lots of garlic, cumin, coriander (the spice, not the herb), tomatoes, and parsley. It is served alongside fried potatoes (that are conveniently cut into the same shape and size as the meat), with a bit of garlicky, tangy yoghurt spooned over it.

While this version is perfectly delicious, there exists another, even yummier incarnation. It began as a mistake. On my first night in Istanbul, I went to Khorasani, a restaurant near the Blue Mosque and Hagia Sofia, and ordered Bodrum çökertme. I liked it so much that I ate it the next night, too, but this time, it tasted different--still good, but different. I didn't realize why until I returned to Florida and decided to cook the dish myself. Looking up recipes, I noticed that the only herb they listed was parsley, yet I remembered an additional flavor, as well. So I started smelling all my herbs and spices, until I finally hit the jackpot with a random French mixture. The mystery ingredient--the "extra" in the first Bodrum çökertme--was tarragon. And I've been including it in the dish since.