The Curious Case of the Clavicle and T1

Bones are remarkable things. Part organic and part inorganic, they structure, support, "feed," and protect your body. They're so sturdy that they survive hundreds of thousands of years before succumbing to fossilization and can withstand temperatures of up to 800 degrees Celsius. They repair surprisingly quickly for such hard, complex stuff, and they're able to tell stories once their owners are no longer able.

They are one of my favorite things in the whole world, which is why I chose forensic anthropology and bioarchaeology as my professions. Yes, I consider myself a practitioner of both subfields, as I currently work at the medical examiner's office but focus my research on stable isotope analyses. My fondness for bones is also the reason I decided to start this column.

Each article of "Sil's Skeletal Spotlight" will explore two very different bones - one I like/love and one I dislike/hate. It will mesh actual scientific (osteological) information with (attempted) humor, as my mind tends to make some very bizarre connections when it comes to skeletal stuff.

So without further preamble, let's meet our first bone.

Clavicle

Colloquially known as the collarbone, each of your two clavicles connects in the front to your breastbone (sternum) and in the back to your shoulder blade (scapula). Its graceful, gently s-curved shape makes it one of my favorites, though some people dislike it because it's initially tricky to side (i.e. determine which side of the body it came from). However, if you run your fingers along your clavicle, you'll feel that it curves upward at the shoulder end and downward at the breastbone end. The word clavicle actually means "little key" in Latin, for it rotates along its axis - apparently like a key - when your arm abducts (raises away from your body).

So we've established it's pretty, at least in my opinion, but what does it really do? Well, as people who've fractured or dislocated their clavicle may know, it anchors your scapula and sternum. Without it, your upper arm would have a severely reduced range of movement. It also protects the blood vessels and nerves that supply the upper limb.

Rather aptly, since this is the first article of the column, the clavicle is the first to begin ossification (turn into bone) in the womb but one of the last to finish. Unlike most other bones, it lacks a center (medullary) cavity, where red and yellow bone marrow are made and stored. It is particularly significant to forensic anthropology because it can be used to determine biological sex, usually when the skull or pelvis isn't available.

Another reason I love the clavicle is because of the reactions it elicits from students in osteology (study of bones) classes. Everyone knows when someone's on the clavicle question(s) during an exam, because he or she would be touching his or her own collarbone with a look of either deep concentration or confusion, depending on the person. Usually, this is followed by a triumphant smile and speedy writing (you're allotted one minute per question), but I've witnessed my fair share of prolonged confused expressions. Like I said, some people have difficulty siding it.

T1

In contrast to the clavicle, the first thoracic vertebra gives me nightmares. And I'm not being facetiously hyperbolic. I have legitimately had nightmares that involved the T1, mocking me during a skeletal examination. The reason for my hatred of it will become apparent quite soon.

The "T" stands for thoracic, which refers to the thorax, the area between your neck and waist, and the "1" obviously denotes that it's the first of twelve thoracic vertebrae. They differ from your cervical (neck) and lumbar (lower back) vertebrae with the presence of a long, downward sloping protrusion called a spinous process or spine. They differ in other ways, of course, but explaining those would involve getting into the anatomy of cervical and lumbar verts, which is beyond the scope of this article. As the thoracic vertebrae progress toward the lumbar (downward), their spinous processes become increasingly shorter and blunter.

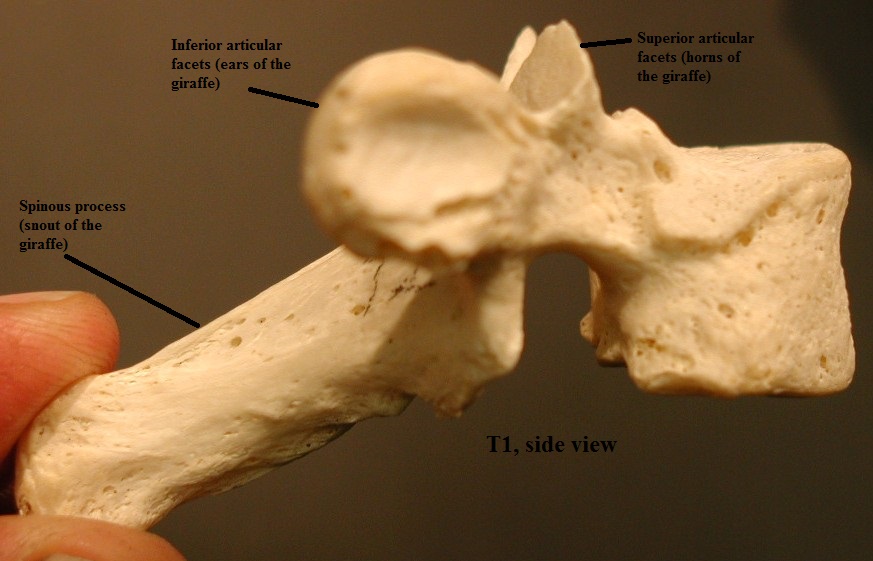

T1 has the longest spinous process, and that's obvious when articulated with the other thoracic verts, but when seen in isolation or as a fragment, identification of it becomes less clear. It was one of the most difficult bones for me to learn, but there's a trick that helped somewhat. When you turn the T1 to the side or towards you, with its spinous process slanting downward, it resembles a giraffe's head. The spinous process is its snout, the superior articulating facets are its little horns, and the inferior articulating facets are its ears. While this resemblance is useful during tests and skeletal examinations, it becomes a bit disturbing when you start dreaming about giraffe-shaped vertebrae talking to you as you're studying them. Worst of all, they weren't very nice.

References:

White TD, Black MT, and Folkens PA. 2011. Human Osteology. Burlington, MA: Academic Press